- Home

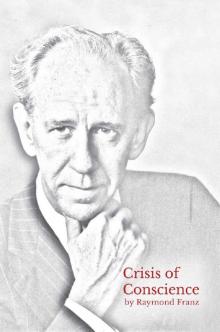

- Raymond Franz

Crisis of Conscience Page 2

Crisis of Conscience Read online

Page 2

What is here described, then, is not merely a “tempest in a teapot,” a major quarrel in a minor religion. I believe there is much of vital benefit that any person can gain from considering this account. For if the numbers presently involved are comparatively small; the issues are not. They are far-reaching questions that have brought men and women into similar crises of conscience again and again throughout history.

At stake is the freedom to pursue spiritual truth untrammeled by arbitrary restrictions and the right to enjoy a personal relationship with God and his Son free from the subtle interposition of a priestly nature on the part of some human agency. While much of what is written may on the surface appear to be distinctive of the organization of Jehovah’s Witnesses, in reality the underlying, fundamental issues affect the life of persons of any faith that takes the name Christian.

The price of firmly believing that it is “neither safe nor right to act against conscience” has not been small for the men and women I know. Some find themselves suddenly severed from family relationships as a result of official religious action—cut off from parents, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, even from grandparents or grandchildren. They can no longer enjoy free association with longtime friends for whom they feel deep affection; such association would place those friends in jeopardy of the same official action. They witness the blackening of their own good name—one that it has taken them a lifetime to earn—and all that such name has stood for in the minds and hearts of those who knew them. They are thereby deprived of whatever good and rightful influence they might exercise on behalf of the very people they have known best in their community, in their country, in all the world. Material losses, even physical mistreatment and abuse, can be easier to face than this.

What could move a person to risk such a loss? How many persons today would? There are, of course (as there have always been), people who would risk any or all of these things because of stubborn pride, or to satisfy the desire for material gain, for power, prestige, prominence, or simply for fleshly pleasure. But when the evidence reveals nothing indicating such aims, when in fact it shows that the men and women involved recognized that just the opposite of those goals was what they could expect—what then?

What has happened among Jehovah’s Witnesses provides an unusual and thought-provoking study in human nature. Besides those who were willing to face excommunication for the sake of conscience, what of the larger number, those who felt obliged to share in or support such excommunications, to allow the family circle to be broken, to terminate long-standing friendships? There is no question about the sincerity of many of these persons, or that they felt and still feel distress from carrying out what they deemed a necessary religious duty. What convictions and reasoning motivated them?

Notably, as regards the cases here dealt with, many if not most of those involved are persons who have been associated with Jehovah’s Witnesses for twenty, thirty, forty or more years. Rather than a “fringe element” they have more frequently been among the more active, productive members of the organization.

They include persons who were prominent members of the Witnesses’ international headquarters staff at Brooklyn, New York; men who were traveling superintendents and elders; women who spent long years in missionary and evangelistic work. When they first became Witnesses, they had often cut off all previous friendships with persons of other faiths, since such “outside” associations are discouraged among Jehovah’s Witnesses. For the rest of their life their only friends have been among those of their religious community. Some had built their whole life plans around the goals set before them by the organization, letting these control the amount of education they sought, the type of work they did, their decisions as to marriage, and whether they had children or remained childless. Their “investment” was a large one, involving some of life’s most precious assets. And now they have seen all this disappear, wiped out in a matter of a few hours.

This is, I believe, one of the strange features of our time, that some of the most stringent measures to restrain expressions of personal conscience have come from religious groups once noted for the defense of freedom of conscience.

The examples of three men—each a religious instructor of note in his particular religion, with each situation coming to a culmination in the same year—illustrate this:

One, for more than a decade, wrote books and regularly gave lectures presenting views that struck at the very heart of the authority structure of his religion.

Another gave a talk before an audience of more than a thousand persons in which he took issue with his religious organization’s teachings about a key date and its significance in fulfillment of Bible prophecy.

The third made no such public pronouncements. His only expressions of difference of viewpoint were confined to personal conversations with close friends.

Yet the strictness of the official action taken toward each of these men by their respective religious organizations was in inverse proportion to the seriousness of their actions. And the source of the greatest severity was the opposite of what one might expect.

The first person described is Roman Catholic priest Hans Küng, professor at Tübingen University in West Germany. After ten years, his outspoken criticism, including his rejection of the doctrinal infallibility of the Pope and councils of bishops, was finally dealt with by the Vatican itself and, as of 1980; the Vatican removed his official status as a Catholic theologian. Yet he remains a priest and a leading figure in the university’s ecumenical research institute. Even students for the priesthood attending his lectures are not subject to church discipline.4

The second is Australian-born Seventh Day Adventist professor Desmond Ford. His speech to a layman’s group of a thousand persons at a California college, in which he took issue with the Adventist teaching about the date 1844, led to a church hearing. Ford was granted six months leave of absence to prepare his defense and, in 1980, was then met with by a hundred church representatives who spent some fifty hours hearing his testimony. Church officials then decided to remove him from his teaching post and strip him of his ministerial status. But he was not disfellowshipped (excommunicated) though he has published his views and continues to speak about them in Adventist circles.5

The third man is Edward Dunlap, who was for many years the Registrar of the sole missionary school of Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Watchtower Bible School of Gilead, also a major contributor to the organization’s Bible dictionary (Aid to Bible Understanding [now titled Insight on the Scriptures]) and the writer of its only Bible commentary (Commentary on the Letter of James). He expressed his difference of viewpoint on certain teachings only in private conversation with friends of long standing. In the spring of 1980, a committee of five men, none of them members of the organization’s Governing Body, met with him in secret session for a few hours, interrogating him on his views. After over forty years of association, Dunlap was dismissed from his work and his home at the international headquarters and disfellowshipped from the organization.

Thus, the religious organization that, for many, has long been a symbol of extreme authoritarianism showed the greatest degree of tolerance toward its dissident instructor; the organization that has taken particular pride in its fight for freedom of conscience showed the least.

Herein lies a paradox. Despite their intense activity in door-to-door witnessing, most people actually know little about Jehovah’s Witnesses aside from their position on certain issues of conscience. They have heard of their uncompromising stand in refusing to accept blood transfusions, their refusal to salute any flag or similar emblem, their firm objection to performance of military service, their opposition to participation in any political activity or function. Those familiar with legal cases know that they have taken some fifty cases to the Supreme Court of the United States in defense of their freedom of conscience, including their right to carry their message to people of other beliefs even in the face of considerable opposition and objections. In lands

where constitutional liberties protect them, they are free to exercise such rights without hindrance. In other countries they have experienced severe persecution, arrests, jailing, mobbing, beatings, and official bans prohibiting their literature and preaching.

How, then, is it the case that today any person among their members who voices a personal difference of viewpoint as to the teachings of the organization is almost certain to face judicial proceedings and, unless willing to retract, is liable for disfellowshipment? How do those carrying out those proceedings rationalize the apparent contradiction in position? Paralleling this is the question of whether endurance of severe persecution and physical mistreatment at the hand of opposers is, of itself, necessarily evidence of belief in the vital importance of staying true to conscience, or whether it can simply be the result of concern to adhere to an organization’s teachings and standards, violation of which is known to bring severe disciplinary action.

Some may say that the issue is really not as simple as it is here presented, that there are other crucial matters involved. What of the need for religious unity and order? What of the need for protection against those who spread false, divisive and pernicious teachings? What of the need for proper respect for authority?

To ignore those factors would admittedly show an extreme, blindly unbalanced, attitude. Who can challenge the fact that freedom, misused, can lead to irresponsibility, disorder, and can end in confusion, even anarchy? Patience and tolerance likewise can become nothing more than an excuse for indecision, non-action, a lowering of all standards. Even love can become mere sentimentality, misguided emotion that neglects to do what is really needed, with cruel consequences. All this is true and is what those focus on who would impose restraints on personal conscience through religious authority.

What, however, is the effect when spiritual “guidance” becomes mental domination, even spiritual tyranny? What happens when the desirable qualities of unity and order are substituted for by demands for institutionalized conformity and by legalistic regimentation? What results when proper respect for authority is converted into servility, unquestioning submission, and an abandonment of personal responsibility before God to make decisions based on individual conscience?

Those questions must be considered if the issue is not to be distorted and misrepresented. What follows in this book illustrates in a very graphic way the effect these things have on human relationships, the unusual positions and actions persons will take who see only one side of the issue, the extremes to which they will go to uphold that side. The organizational character and spirit manifest in the 1980s, continued essentially unchanged in the1990s, and remains the same in this year 2008.

Perhaps the greatest value in seeing this is, I feel, that it can help us discern more clearly what the fundamental issues were in the days of Jesus Christ and his apostles, and understand why and how a tragic deviation from their teachings and example came, so subtly, with such relative ease, in so brief a span of time. Those who are of other religious affiliations and who may be quick to judge Jehovah’s Witnesses would do well to ask first about themselves and about their own religious affiliation in the light of the issues involved, the basic attitudes that underlie the positions described and the actions taken.

To search out the answers to the questions raised requires going beyond the individuals affected into the inner structure of a distinctive religious organization, into its system of teaching and control, discovering how the men who direct it arrive at their decisions and policies, and to some extent investigating its past history and origins. Hopefully the lessons learned can aid in uncovering the root causes of religious turmoil and point to what is needed if persons trying to be genuine followers of God’s Son are to enjoy peace and brotherly unity.

1These were Luther’s concluding words in making his defense at the Diet of Worms, Germany, in April of 1521.

2Acts 4:19, 20, RSV.

31 Corinthians 11:3.

4They simply receive no academic credit for such attendance.

5In conversation with Desmond Ford at Chattanooga, Tennessee, in 1982, he mentioned that by then more than 120 ministers of the Seventh Day Adventist church had either resigned or been “defrocked” by the church because they could not support certain teachings or recent actions of the organization.

2

CREDENTIALS AND CAUSE

I am speaking the truth as a Christian, and my own conscience, enlightened by the Holy Spirit, assures me it is no lie. . . . For I could even pray to be outcast from Christ myself for the sake of my brothers, my natural kinsfolk.

— Romans 9:1, 3. New English Bible.

WHAT has thus far been said gives, I believe, good reason for the writing of this book. The question may remain as to why I am the one writing it.

One reason is my background and the perspective it gives. From babyhood up into my sixtieth year, my life was spent in association with Jehovah’s Witnesses. While others, many others, could say the same, it is unlikely that very many of them had the range of experience that happened to be my lot during those years.

A reason of greater weight is that circumstances brought to my knowledge information to which the vast majority of Jehovah’s Witnesses have absolutely no access. The circumstances were seldom of my own making. The information was often totally unexpected, even disturbing.

A final reason, resulting from the previous two, is that of conscience. What do you do when you see mounting evidence that people are being hurt, deeply hurt, with no real justification? What obligation do any of us have—before God and toward fellow humans—when he sees that information is withheld from people to whom it could be of the most serious consequence? These were questions with which I struggled.

What follows expands on these reasons.

In many ways I would much prefer passing over the first of these since it necessarily deals with my own “record.” The present situation seems to require its presentation, however, somewhat in the way circumstances obliged the apostle Paul to set out his record of personal experiences for Christians in Corinth and afterward to say to them:

I am being very foolish, but it was you who drove me to it; my credentials should have come from you. In no respect did I fall short of these superlative apostles, even if I am a nobody [even though I am nothing, New International Version].1

I make no pretense of being a Paul, but I believe that my reason and motive at least run parallel with his.

My father and mother (and three of my four grandparents) were Witnesses, my father having been baptized in 1913 when the Witnesses were known simply as Bible Students. I did not become an active Witness until I was sixteen in 1938. Though still in school, I was before long spending from twenty to thirty hours a month in “witnessing” from door to door, standing on street corners with magazines, putting out handbills while wearing placards saying “Religion is a snare, the Bible tells why. Serve God and Christ the King.”

That year, 1938, I had attended a Witness assembly in Cincinnati (across the Ohio River from our home) and listened to Judge Joseph F. Rutherford, the president of the Watch Tower Society, speak from London, England, by radiotelephone communication. In a major talk entitled “Face the Facts,” Rutherford’s opening words included this:

That appealed to me as a worthwhile principle to follow in life. I felt receptive to the facts he would present.

World War II had not yet begun as of that year, but Nazism and Fascism were growing in power and posing an increasing threat to democratic lands. Among major points emphasized in the Watch Tower president’s talk were these:

God has made it clearly to be seen by those who diligently seek the truth that religion is a form of worship but which denies the power of God and turns men away from God. . . . Religion and Christianity are therefore exactly opposite to each other. . . .3

According to the prophecy of Jesus, what are the things to be expected when the world comes to an end? The answer is world war, famine, pestilence, distress of na

tions, and amongst other things mentioned the appearance of a monstrosity on the earth. . . . These are the indisputable physical facts which have come to pass proving that Satan’s world has come to an end, and which facts cannot be ignored. . . .4

Now Germany is in an alliance with the Papacy, and Great Britain is rapidly moving in that direction. The United States of America, once the bulwark of democracy, is all set to become part of the totalitarian rule. .

. . Thus the indisputable facts are, that there is now in the earth Satan’s dictatorial monstrosity, which defies and opposes Jehovah’s kingdom. . . . The totalitarian combine is going to get control of England and America. You cannot prevent it. Do not try. Your safety is on the Lord’s side. . . .5

I have italicized statements that particularly engraved themselves on my mind at that time. They created in me an intensity of feeling, of near agitation that I had not experienced before. Yet none of them today form part of Witness belief.

Rutherford’s other major talk, “Fill the Earth,” developed the view that as of 1935 God’s message, till then directed to persons who would reign with Christ in heaven, a “little flock,” was now being directed to an earthly class, the “other sheep,” and that after the approaching war of Armageddon these would procreate and fill the earth with a righteous offspring. Of these he said:

They must find protection in God’s organization, which shows that they must be immersed, baptized or hidden in that organization. The ark, which Noah built at God’s command, pictured God’s organization. . . .6

Pointing out that Noah’s three sons evidently did not begin to produce offspring until two years after the Flood, the Watch Tower president then made an application to those with earthly hopes in modern times, saying:

Joseph Rutherford spoke forcefully and with a distinctive cadence of great finality. These were facts, even “indisputable facts,” solid truths on which to build life’s most serious plans. I was deeply impressed with the importance of the organization as essential to salvation, also that the work of witnessing must take precedence over, or at least militate against, such personal interests as marriage and childbearing.8

Crisis of Conscience

Crisis of Conscience