- Home

- Raymond Franz

Crisis of Conscience Page 18

Crisis of Conscience Read online

Page 18

Most of all I have asked myself whether, if found in a similar circumstance in Bible times, Abraham, Daniel, Jesus and his apostles, or early Christians, would have viewed submission to such government demands in the way the organization has presented it? Granted, there was no actual law passed in Malawi requiring the purchase of the card, but would such a technicality have been viewed by Christ Jesus as crucial in the face of the statements made nationwide by the ruling authorities?4 How would Christians of the first century have viewed it in the light of the apostle’s exhortation, “Render to all their dues, to him who calls for the tax, the tax; for him who calls for the tribute, the tribute; to him who calls for fear, such fear; to him who calls for honor, such honor”?5

To submit to such demands, then as now, would certainly be condemned by some as “compromise,” a “caving in” to the demands of the political authorities. But I am sure that in Jesus’ day there were many devout Jews who felt that to accede to the demands of a military officer of the hated Roman Empire that one carry certain baggage for a mile would be just as detestable; many would have suffered punishment and mistreatment rather than submit. Yet Jesus said to submit and to go, not just one mile, but two!6 To many of his listeners this counsel was doubtless repugnant, smacking of craven surrender instead of unbending adherence to a position of no collaboration with alien, Gentile powers.

Of one thing I eventually became certain and that was that I would want to be very confident that the position adopted was solidly founded on God’s Word, and not on mere human reasoning, before I could think of advocating it or promulgating it, particularly in view of the grave consequences it produced. I no longer felt confident that the Scriptures did give such clear and unequivocal support to the policy taken toward the situation in Malawi. I could see how one might feel impelled by conscience to refuse to purchase such a card and, if that were the case, then one should refuse, in harmony with the apostle’s counsel at Romans, chapter fourteen, verses 1 to 3 and verse 23.7 But I could not see the basis for anyone’s imposing his conscience on another in this matter, nor of presenting such position as a rigid standard to be adhered to by others, particularly without greater support from Scripture and fact.

Against such background of circumstances relating to Malawi, consider now the information that came to light during the Governing Body’s discussion of the alternative service issue. Many of the statements made by members arguing this issue reflected the strict, unyielding attitude encouraged on the part of the Malawian Witnesses. Statements such as these were made by those opposing change in the existing alternative service policy:

Even if there is the slightest suggestion of compromise, or a doubt, we should not do it.

There must be no compromise. . . . Again, it needs to be made clear that a stand of neutrality, as “no part of the world,” keeping clear of those arms of the world—religion, politics and the military—supporting them neither directly nor indirectly, is the stand that will be blessed by Jehovah. We want no grey areas, we want to know exactly where we stand as non-compromising Christians.8

. . . doing civilian work in lieu of military duty is . . . a tacit or implied acknowledgement of one’s obligation to Caesar’s war machine. . . . A Christian therefore cannot be required to support the military establishment either directly or indirectly.9

For one of Jehovah’s Witnesses to tell a judge that he is willing to accept work in a hospital or similar work would be making a “deal” with the judge, and he would be breaking his integrity with God.10

To accept the alternative civil service is a form of moral support to the entire arrangement.11

We should have a united stand all over the world. We should be decisive in this matter. . . . If we were to allow the brothers this latitude we would have problems. . . . the brothers need to have their consciences educated.”12

If we yield to Caesar then there is no witness given.13

Those who accept this substitute service are taking the easy way out.14

What I find amazing is that at the same time these strong, unyielding statements were made, those making them were aware of the situation then existing in Mexico. When I supplied each member of the Governing Body with a copy of the survey of Branch Committee reports on alternative service, I included material sent in by the Branch Committee of Mexico. It included this portion dealing with the “Identity Cartilla for Military Service” (“cartilla” means a certificate):

What was the position of Jehovah’s Witnesses as to such “illegal operations” in connection with this law? The Branch Committee’s letter goes on to say:

Put briefly, in Mexico men of draft age were required to undergo a specified period of military training during a period of one year. Upon registration the registrant received a certificate or “cartilla” with places for noting down attendance at weekly military instruction classes. It was illegal and punishable for any official to fill in this attendance record if the registrant had not actually attended. But officials could be bribed to do so and many men in Mexico did this bribing. According to the Branch Office Committee this was also a common practice among Jehovah’s Witnesses in Mexico. Why? Note what the Branch statement goes on to say:

What was the information provided by the Society that the Branch Office in Mexico had been following for years? How was it supplied? How did the information provided compare with the position taken in Malawi and with the strong, unbending statements made by Governing Body members against even “the slightest suggestion of compromise,” against any form of “moral support,” either “directly or indirectly,” of the military establishment?

I made a trip to Mexico within a few days of the November 15, 1978, Governing Body session which had resulted in a stalemate on the alternative service issue. I was assigned to visit the Mexico Branch Office as well as those of several Central American countries. During my meeting with the Mexico Branch Committee they brought up the practice described in their report. They said that the terrible persecution endured by Jehovah’s Witnesses in Malawi due to their refusal to buy a party card had caused many Witnesses in Mexico to feel disturbed in their conscience. They made clear, however, that their counsel to the Mexican Witnesses was fully in accord with the counsel the Branch Office had received from the world headquarters. What was that counsel? It may be difficult for some to believe that the counsel given was actually given, but this is the evidence presented by the Branch Committee. First comes this letter:

What you have just read is a copy of a letter from the Mexico Branch to the president of the Society, the second paragraph of which shows the question the Branch presented for answer on the paying of bribes for a falsified military document. (The copy is of the carbon copy retained by the Branch which, unlike the original, customarily did not bear a signature.)

What reply did their inquiry receive? The Society’s answer came in a two-page letter dated June 2, 1960. The second page dealt with the military issue written about. This is that page as presented to me by the Mexico Branch Committee, containing the Society’s counsel on their questions.

Although the Branch’s letter had been directed to President Knorr, the reply, bearing the stamped corporation signature, was evidently written by Vice-President Fred Franz, who, as stated earlier, was regularly called upon by President Knorr to formulate policy on matters of this type. The language is typically that of the vice president, not that of the president.

The expressions this letter contains are worth noting. It would be worthwhile to take the time to go back and compare them with the earlier listed statements by Governing Body members arguing the alternative service issue, statements made then that neither minced words nor sought nicety of language but which were often blunt, even hard-hitting.

In this Society reply to the Mexico query, the word “bribe” is avoided, replaced by euphemistic reference to “a money transaction,” the “payment of a fee.” Emphasis is placed on the fact that the money went to an individual rather than to the “milita

ry establishment,” apparently indicating that this somehow improved the moral character of the “transaction.” The letter speaks of the arrangement being “current down there” and says that as long as inspectors do not inquire about the “veracity of matters” it can be “passed by” for the “accruing advantages.” It ends with mention of maintaining integrity in some possible future “determinative test.”

If this same message were put in the kind of language heard from Governing Body members in the sessions debating alternative service, I believe it would read more like the following:

Paying bribes to corrupt officials is done by Jehovah’s Witnesses in other Latin American countries. If the men of the war machine are willing to be bribed, the risk is theirs. At least you are not paying the bribe to the actual war machine itself—only to a colonel or other officer who pockets the bribe for himself. If brothers’ consciences will let them make a ‘deal’ with some official who is ‘on the take,’ we will not object. Of course, if there is trouble they should not look to us for help. Since everyone down there is doing it and inspectors make no issue about the faked documents, then you at the Branch Office can just look the other way too. If war comes that will be time enough to worry about facing up to the issue of neutrality.

Faithfully yours in the Kingdom ministry,

It is not my intent to be sarcastic and I do not believe what is set out constitutes sarcasm. I believe it to be a fair presentation of the Society’s counsel to the Mexican Branch Office put in down-to-earth language, free from euphemisms—language more like that used in the Governing Body sessions mentioned.

One reason why this information was so personally shocking to me was that, at the very time the letter stating that the Society had “no objection” if Witnesses in Mexico, faced with a call to military training, chose to “extricate themselves by a money payment,” there were scores of young men in the Dominican Republic spending precious years of their life in prison—because they refused the identical kind of training. Some, such as Leon Glass and his brother Enrique, were sentenced two or three times for their refusal, passing as much as a total of nine years of their young manhood in prison. The Society’s president and vice president had travelled to the Dominican Republic during those years and had even been made visits to the prison where many of these men were detained. How the situation of these Dominican prisoners could be known by them and yet such a double standard be applied is incomprehensible to me.

Four years after that counsel was given to Mexico the first eruption of violent attacks against Jehovah’s Witnesses in Malawi took place (1964) and the issue of paying for a party card arose. The position taken by the Malawi Branch Office was that to do so would be a violation of Christian neutrality, a compromise unworthy of a genuine Christian. The world headquarters knew that this was the position taken. The violence subsided after a while and then broke out again in 1967, so fiercely that thousands of Witnesses were driven into flight from their homeland. The reports of horrible atrocities in increasing number came flooding in to the world headquarters.

What effect did it have on the men leading the organization and on their consciences as regards the position taken in Mexico? In Malawi Witnesses were being beaten and tortured, women were being raped, homes and fields were being destroyed, and entire families were fleeing to other countries—determined to hold to the organization’s stand that to pay for a party card would be a morally traitorous act. At the same time, in Mexico, Witness men were bribing military officials to complete a certificate falsely stating that they had fulfilled their military service obligations. And when they went to the Branch Office, the staff there followed the Society’s counsel and said nothing to indicate in any way that this practice was inconsistent with organizational standards or the principles of God’s Word. Knowing this, how were those in the position of highest authority in the organization affected? Consider:

Nine years after the Mexico Branch wrote their first letter they wrote a second letter, dated August 27, 1969, also addressed to President Knorr. This time they emphasized a particular point they felt had been overlooked. Set out are pages three and four of the letter provided me by the Branch Committee. I have underlined the main point the Branch focuses on.

The reply sent, dated September 5, 1969, and shown on the next page, bears the stamp of the New York Corporation but the symbol before the date indicates that it was written by the president through a secretary (“A” being the symbol for the president, and “AG” being the symbol held by one of his secretaries). Keeping in mind that the world headquarters was fully informed of the horrible suffering Jehovah’s Witnesses in Malawi had already undergone in 1964 and in 1967 because they steadfastly refused to pay for the party card being actively promoted by the government of their country, consider the reply of September 5, 1969, sent to the Mexico Branch’s inquiry.

What makes all this so utterly incredible is that the organization’s position on membership in the military has always been identical to its position on membership in a “political” organization. In both cases any Witness who enters such membership is automatically viewed as “disassociated.” Yet the Mexico Branch Committee had made crystal clear that all these Witnesses who had obtained the completed certificate of military service (by means of a bribe) were now placed in the first reserve of the military. The Witnesses in Malawi risked life and limb, homes and lands, to adhere to the stance adopted by the organization for their country. In Mexico there was no such risk involved, yet a policy of the utmost leniency was applied. There, Witness men could be members of the first reserves of the army and yet be Circuit or District Overseers, members of the Bethel family! The report from the Branch Committee in response to the survey makes this clear (as well as showing how common the practice of bribing to get the certificate was among the Witnesses). It goes on to say:

Literally thousands of Witnesses in Mexico knew the truth of the situation as described. All the members of the Mexico Branch Committee knew it. And all those then members of the Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses knew what the stated position of the world headquarters was on the matter. Yet outside of Mexico very few people had any idea of what was said. Probably no one among the Witnesses in Malawi was aware of this remarkable policy.

I cannot imagine a more obvious double standard. Nor can I conceive of more twisted reasoning than that which allowed for the position taken in Mexico and at the same time argued so strenuously and so dogmatically that to accept alternative service is condemnable because it is “viewed by the government as fulfillment of military service’ is a “tacit or implied acknowledgement of Caesar’s war machine.” The same men who made those statements in Governing Body sessions and insisted that “we want no grey areas” and that “the brothers need to have their consciences educated,” said this knowing that the common practice among Jehovah’s Witnesses in Mexico for over twenty years had been to pay a bribe for a certificate saying they had fulfilled their military service, a practice that the world headquarters had officially stated was ‘up to their conscience.’

Despite this, some members (and, happily, in several of the sessions it was only a minority) strenuously argued for the traditional position—a position that labeled a man as “disassociated” if he answered a judge’s question about working in a hospital by responding simply and truthfully that his conscience would allow this. They favored that traditional policy while knowing that in Mexico men who were elders, Circuit Overseers, District Overseers and Branch Office staff personnel, had bribed officials to get their completed military service certificate stating that they were now in the first reserves of the military, the “war machine.”

One Governing Body member, arguing for the traditional stand, had quoted a member of the Denmark Branch Committee, Richard Abrahamson, as having said regarding alternative service, “I shudder to think of putting these young men on their own choice.” Yet the official counsel sent by the headquarters organization to the Mexico Branch was that young brothe

rs’ paying a bribe for a falsified document placing them in the first reserves was “for them to worry about, if they are worried. It is not for the Society’s office to be worried about.” Later the letter stated that, “There is no reason to decide another man’s conscience.”

Why was not the same position taken toward those in Malawi? I seriously doubt that the majority of Witnesses there would have arrived at the same conclusions as the Branch Office personnel did. It is equally doubtful that there was a single native of Malawi (then Nyasaland) among those Branch representatives, who formulated that policy decision, to be obeyed by the Malawian Witnesses.

Is there no responsibility resting upon those in authority within the organization for what amounts to a grotesque disparity of direction given?

Notably, as regards the failure of the Malawian authorities to uphold the high principles of their Constitution, the Watch Tower Society had stated that the “ultimate responsibility” for the injustice must be placed on President Banda, saying:

The same standard by which the organization judged the actions of the Malawian authorities should certainly apply to the Watch Tower organization also. If the Governing Body, not only knowing what had been said about the Malawian authorities and their responsibility, but also knowing of the organization’s stand taken in Mexico, really believed that the position promulgated among the brotherhood in Malawi was the right one, then they should certainly have felt impelled to reject the position taken in Mexico. To uphold the rigid position taken in Malawi they should have been positively convinced of the rightness of that stand, with no doubts about it as being the only stand for a true Christian to take, one soundly and solidly based on God’s Word. To countenance in any way the position taken in Mexico would be to deny that they held such a conviction.

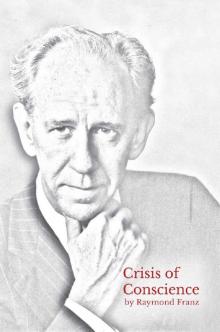

Crisis of Conscience

Crisis of Conscience