- Home

- Raymond Franz

Crisis of Conscience Page 11

Crisis of Conscience Read online

Page 11

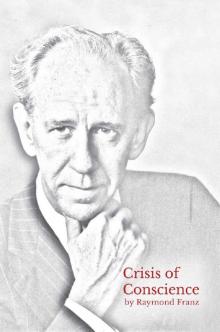

Governing Body members in 1975. First row: Ewart Chitty, Fred Franz, Nathan Knorr, George Gangas, John Booth, Charles Fekel. Second row: Dan Sydlik, Raymond Franz, Lloyd Barry, William Jackson, Grant Suiter, Leo Greenlees. Back row: Theodore Jaracz, Lyman Swingle, Milton Henschel, Karl Klein, Albert Schroeder.

At certain points in the discussion I expressed my understanding that other matters of a spiritual nature were likewise the responsibility of the Body. (I could not personally harmonize the existing monarchical arrangement with Jesus’ statement that “all you are brothers” and “your Leader is one, the Christ”; that “the rulers of the nations lord it over them and the great men wield authority over them,” but “this is not the way among you.”3 It simply did not seem honest to say what had been said in the 1971 Watchtower articles and then not carry it out.)

In each case of my doing so, however, the president took the remarks very personally, speaking at great length, his voice tense and forceful, saying that ‘evidently some were not satisfied with the way he was handling his job.’ He would go into great detail as to the work he was performing and then would say, “now apparently some don’t want me to handle things anymore” and that perhaps he should “bring it all down here and turn it over to Ray Franz and let him handle it.”

I found it hard to believe that he could so totally miss the essential point of my comments, that I was expressing myself in favor of a body arrangement, not in favor of a transferal of authority from one individual administrator to another individual administrator. Each time I would explain this to him, making plain that what was said was never meant as any kind of personal attack, that I did not feel that ANY one individual should take on the responsibilities under discussion, but rather that my understanding from the Bible and from the Watchtower was that they were matters for a body of persons to deal with. I said again and again that if it were a matter of one person handling everything, then he would be my choice; that I felt he had simply been doing what he felt he should do and what had always been done in the past; that I had no complaint about his doing so.

This did not seem to make any impression, however, and, realizing that anything I said along this line would simply provoke anger, after a few attempts I gave up. On these occasions the remainder of the Body members sat, observed and said nothing. What happened a few years later therefore came as a surprise.

Nothing further developed until the year 1975. Consider now what the organization’s 1993 history book Jehovah’s Witnesses—Proclaimers of God’s Kingdom relates as to what then took place, an event described as “one of the most significant organizational readjustments in the modern-day history of Jehovah’s Witnesses.” On pages 108 and 109, we read:

The book thus leads the reader to believe that the failing health of the Society’s third president, Nathan Knorr, in late 1975 was somehow involved in this major event in the organization’s history, was perhaps a motivating reason for it. All the men who were on the Governing Body at that time know that this picture is not true. Knorr’s health problem in reality became evident after the issue had arisen leading to the change, and hence was purely coincidental. It neither gave rise to the issue nor was it a factor in the Governing Body discussions and decisions. There is a clear lack of candor in the picture presented.

What then did happen?

In 1975, two Bethel Elders (Malcolm Allen, a senior member of the Service Department and Robert Lang, the Assistant Bethel Home Overseer) wrote letters to the Governing Body expressing concern over certain conditions prevalent within the headquarters staff, specifically referring to an atmosphere of fear generated by those having oversight and a growing feeling of discouragement and resultant discontent.

At that time anyone applying for service at headquarters (“Bethel Service”) had to agree to stay a minimum of four years. Most of the applicants were young men, 19 and 20 years of age. Four years equaled one-fifth of the life they had thus far lived. When at the meal tables, I often asked the person next to me, “How long have you been here?” In the ten years I had by now spent at headquarters I had never heard one of these young men respond by saying in round figures, “About a year’ or “about two years.” Invariably the answer was, “One and seven,” “two and five,” “three and one” and so forth, always giving the year or years and the exact number of months. I could not help but think of the way men serving a prison sentence often follow a similar practice of marking off time.

Generally it was difficult to get these young men to express themselves about their service at headquarters. As I learned from friends who worked more closely with them, they were unwilling to say much in an open way since they feared that anything they said that was not positive would cause them to be classed as what was popularly called a “B.A.”, someone with a “bad attitude.”

Many felt like “cogs in a machine,” viewed as workers but not as persons. Job insecurity resulted from knowing that they could be shifted at any time to another work assignment without any previous discussion and often with no explanation for the change made. “Management-employee” lines were clearly drawn and carefully maintained.

The monthly allowance of fourteen dollars often barely covered (and in some cases was less than) their transportation costs going to and from Kingdom Hall meetings. Those whose family or friends were more affluent had no problems as they received outside assistance. But others rarely could afford anything beyond bare necessities. Those from more distant points, particularly those from the western states, might find it virtually impossible to travel and spend vacations with their families, particularly if they came from a poor family. Yet they were regularly hearing greetings passed on to the Bethel Family from members of the Governing Body and others as they traveled around the country and to other parts of the world giving talks. They saw the corporation officers driving new Oldsmobiles bought by the Society and serviced and cleaned by workers like themselves. Their work schedule, then consisting of eight hours and forty minutes each day, and four hours on Saturday morning, combined with attendance at meetings three times a week, plus the weekly “witnessing” activity, seemed to many to make their lives very cramped, routine, tiring. But they knew that to lessen up in any of these areas would undoubtedly put them in the “B.A.” class and result in their being called to a meeting designed to correct their attitude.

The letters by the two Bethel Elders touched on these areas but without going into detail. The president again seemed to feel, unfortunately, that this constituted criticism of his administration. He expressed himself to the Governing Body as wanting a hearing to be held on the matter and on April 2, 1975, this was done. A number of Bethel Elders spoke and many of the earlier-mentioned specifics were there aired. Those speaking did not indulge in personalities and made no demands, but they stressed the need for more consideration of the individual, for brotherly communication and the benefit of letting those close to problems share in decisions and solutions. As the Assistant Bethel Home Overseer, Robert Lang, put it, “we seem more concerned about production than people.” The staff doctor, Dr. Dixon, related that he frequently received visits from married couples distressed due to the inability of the wives to cope with the pressures and keep up with the demanding schedule, many of the women breaking into tears when talking to him.

A week later, April 9, the official “Minutes” of the Governing Body session stated:

Comments were made on the relationship of the Governing Body and the corporations and what was published in the Watchtower of December 15, 1971. It was agreed that a committee of five made up of L. K. Greenlees, A. D. Schroeder, R. V. Franz, D. Sydlik, and J. C. Booth go into matters concerning this subject and the duties of the officers of the corporations and related matters and take into consideration the thoughts of N. H. Knorr, F. W. Franz and G. Suiter who are officers of the two societies, and then bring recommendations. The whole idea is to strengthen the unity of the organization.

At a session three weeks later, April 30, President Kno

rr surprised us by making a motion that thenceforth all matters be decided by a two-thirds vote of the active membership (which by then numbered seventeen).4 Following this, the official “Minutes” of that session relate:

L. K. Greenlees then began his report from the committee of five on Brother Knorr’s request to tell him what he should do.5 The committee considered the Watchtower of December 15, 1971, paragraph 29 very carefully, also page 760. The committee feels that today the Governing Body should be directing the corporations and not the other way around. The corporations should recognize that the Governing Body of seventeen members has the responsibility to administer the work in the congregations throughout the world. There has been a delay of putting the arrangement into effect at Bethel as compared to the congregations. There has been confusion. We do not want a dual organization.

There followed a lengthy discussion of questions relating to the Governing Body and the corporations and to the president, with comments by all members present. At the close of the day a motion was proposed by N. H. Knorr, followed by a comment by E. C. Chitty. L. K. Greenlees also presented a motion. It was agreed that the three should be Xeroxed and copies given to all members and meet again the next day at 8 a.m. There would be time to pray over the matter which is so important.

The Xeroxed motions referred to read as follows:

N. H. Knorr: “I move the Governing Body take over responsibility of looking after the work directed in the Charter of the Pennsylvania Corporation and assume the responsibilities set out in the Charter of the Pennsylvania Corporation and all other corporations throughout the world used by Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

E. C. Chitty said: “To ‘take over’ means relieve the other party. I believe for my part the responsibility stays as it is. Rather it would be right to say ‘supervise the responsibility.’”

L. K. Greenlees said: “I move that the Governing Body undertake in harmony with the Scriptures the full responsibility and authority for the administration and supervision of the worldwide association of Jehovah’s Witnesses and their activities; that all members and officers of any and all corporations used by Jehovah’s Witnesses will act in harmony with and under direction of this Governing Body; that this enhanced relationship between the Governing Body and the corporations go into effect as soon as can reasonably be done without hurt or damage to the Kingdom Work.”

On the next day, May 1, 1975, there was again a long discussion. In particular the vice president (who had written the Watchtower articles referred to) objected to the proposals made and to any change in the existing setup, any reduction of the corporation president’s authority. (This brought to mind, and was in harmony with, his remarks to me back in 1971 that he thought Jesus Christ would direct the organization through a single person on down to the time when the New Order came.) He made no comment on the evident contradiction between the presentation made in the Watchtower articles (and their bold statements about the Governing Body using the corporations as mere instruments) and the three motions made, each of which showed that the makers (including the president himself) recognized that the Governing Body did not at that time supervise the corporations.

Discussion went back and forth. A turning point seemed to come with remarks made by Grant Suiter, the crisp-speaking secretary-treasurer of the Society’s principal corporations. Different from the comments made till then by those favoring a change, his expressions were quite personal, seemingly the release of a long pent-up feeling about the president, whom he directly named. While discussing the authority structure he made no specific charges, except as regards the right to make a certain change in his personal room that he had requested and had been denied, but as he went on his face became flushed, his jaw muscles flexed and his words became more intense. He closed with the remark:

Grant Suiter

I say if we are going to be a Governing Body, then let’s get to governing! I haven’t been doing any governing till now.

Those words hit me hard enough that I am satisfied that I have remembered and recorded them as said. Whether they were meant to convey the sense they did is, of course, beyond my knowing and they may well have been merely a momentary outburst, not indicative of any heartfelt motive. At any rate they served to make me think very seriously about the matter of right motivation and I felt considerable concern that whatever should come of this whole affair might be the result of a sincere desire on the part of all involved to hold more closely to Bible principles and patterns and not for any other reason. I found the whole session disturbing, mainly because the general spirit did not seem to conform to what one would expect of a Christian body. However, shortly after these last-mentioned comments by the secretary-treasurer, Nathan Knorr evidently reached a decision and made a lengthy statement, taken down in shorthand by Milton Henschel, who had made certain suggestions himself and who then acted as secretary for the Body.6 As recorded in the official “Minutes” the president’s statement included these expressions:

I think it would be a very good thing for the Governing Body to follow through along the lines that Brother Henschel has mentioned and design a program having in mind what the Watchtower says, that the Governing Body is Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses. I am not going to argue for or against it. In my opinion it is not necessary. The Watchtower has stated it.

It will be the Governing Body who will have overall guiding power and influence. They will take their responsibility as Governing Body and direct through different divisions they will set up and they will have an organization.

At the end he said, “I make that a motion.” Somewhat to my surprise, his motion was seconded by F. W. Franz, the vice president. It was adopted unanimously by the Body as a whole.

The bold language of the Watchtower of four years previous seemed about to change from mere words into fact. From the expressions made by the president it appeared that a smooth transition lay ahead. That is the picture of harmonious unity the book Jehovah’s Witnesses—Proclaimers of God’s Kingdom portrays. It was, instead, only a lull preceding the stormiest period of all.

In the months that followed, the appointed “Committee of Five” met with all members of the Governing Body individually and with thirty-three other longtime members of the headquarters staff. By far the majority favored a reorganization. The Committee drew up detailed proposals for an arrangement of Governing Body Committees to handle different facets of the worldwide activity. Of the seventeen Governing Body members personally interviewed, eleven indicated basic approval.

Of the remaining six, George Gangas, a warm and effervescent Greek, and one of the oldest members of the Body, was very uncertain, changeable in his expressions according to the mood of the moment. Charles Fekel, an eastern European, had been a Society Director many years before but had been removed under the charge of having compromised his integrity by the oath he took when obtaining American citizenship. He was now among the most recent appointees to the Body and, of a very mild nature, rarely shared in the discussion, consistently voting whichever way the majority went, and he had little to say on this issue. Lloyd Barry, a New Zealander and also a recent addition to the Body, had come to Brooklyn after a number of years as Branch Overseer of Japan, where Witness activity had seen phenomenal growth. He expressed very strong misgivings about the recommendations, particularly the decentralizing effect it would have as regards the presidency; in a letter dated September 5, 1975, he characterized the recommended change as “revolutionary.” Bill Jackson, a down-to-earth, unassuming Texan (not as rare as some would make it appear), had spent most of his life at headquarters, and, like Barry, he felt that things should be left very much as they were, especially since such good numerical increases had come under the existing administration.

The strongest voices of opposition were those of the president and vice president, the maker and seconder of the motion earlier quoted! They were, in fact, publicly vocal in their opposition.

During the period the appointed “Committee of Five”

was interviewing longtime staff members to get their viewpoint, the president’s turn to preside at the head of the Bethel table for one week came up. For several mornings he used the opportunity to discuss before the 1,200 or more “Bethel Family” members in the several dining rooms (all tied in by sound and television) what he called the “investigation” going on (the Committee of Five’s interviews), saying that “some persons” favored changing things that had been done a certain way for the whole life of the organization. He asked again and again, “Where is their proof that things aren’t working well, that a change is needed?” He said that the “investigation” was endeavoring to “prove this family is bad,” but said he was confident that “a few complainers” would not “overwhelm the joy of the majority.” He urged all to “have faith in the Society,” pointing to its many accomplishments. At one point he said with great force and feeling that the changes some wanted to make as to the Bethel Family and its work and organization “will be made over my dead body.”7

In all fairness to Nathan Knorr, it must be said that he undoubtedly believed that the then-existing arrangement was the right one. He knew that the vice president, the organization’s most respected scholar and the one he relied upon to handle Scriptural matters, felt that way. Knorr was basically an affable person, capable of warmth. When he was not in his president’s “uniform” or role, I genuinely enjoyed my association with him. However, his official position, as is so often the case, did not generally let that side of him be seen and (again, doubtless due to his feeling that the role he carried out was according to God’s will) he inclined to react very quickly and forcefully to any apparent infringement upon his presidential authority. People learned not to do this. For all that, I seriously doubt that Nathan would have gone along with some of the harsh actions that were later to come from the collective body that inherited his presidential authority.

Crisis of Conscience

Crisis of Conscience